Retina

What Is Macular Degeneration?

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a deterioration or breakdown of the eye’s macula. The macula is a small area in the retina — the light-sensitive tissue lining the back of the eye. The macula is the part of the retina that is responsible for your central vision, allowing you to see fine details clearly.

The macula makes up only a small part of the retina, yet it is much more sensitive to detail than the rest of the retina (called the peripheral retina). The macula is what allows you to thread a needle, read small print, and read street signs. The peripheral retina gives you side (or peripheral) vision. If someone is standing off to one side of your vision, your peripheral retina helps you know that person is there by allowing you to see their general shape.

Many older people develop macular degeneration as part of the body’s natural aging process. There are different kinds of macular problems, but the most common is age-related macular degeneration.

With macular degeneration, you may have symptoms such as blurriness, dark areas or distortion in your central vision, and perhaps permanent loss of your central vision. It usually does not affect your side, or peripheral vision. For example, with advanced macular degeneration, you could see the outline of a clock, yet may not be able to see the hands of the clock to tell what time it is.

Causes of macular degeneration include the formation of deposits called drusen under the retina, and in some cases, the growth of abnormal blood vessels under the retina. With or without treatment, macular degeneration alone almost never causes total blindness. People with more advanced cases of macular degeneration continue to have useful vision using their side, or peripheral vision. In many cases, macular degeneration’s impact on your vision can be minimal.

When macular degeneration does lead to loss of vision, it usually begins in just one eye, though it may affect the other eye later.

Many people are not aware that they have macular degeneration until they have a noticeable vision problem or until it is detected during an eye examination.

Types of macular degeneration: dry macular degeneration and wet macular degeneration

There are two types of macular degeneration:

Dry, or atrophic, macular degeneration (also called non-neovascular macular degeneration) with drusen

Most people who have macular degeneration have the dry form. This condition is caused by aging and thinning of the tissues of the macula. Macular degeneration usually begins when tiny yellow or white pieces of fatty protein called drusen form under the retina. Eventually, the macula may become thinner and stop working properly.

With dry macular degeneration, vision loss is usually gradual. People who develop dry macular degeneration must carefully and constantly monitor their central vision. If you notice any changes in your vision, you should tell your ophthalmologist right away, as the dry form can change into the more damaging form of macular degeneration called wet (exudative) macular degeneration. While there is no medication or treatment for dry macular degeneration, some people may benefit from a vitamin therapy regimen for dry macular degeneration.

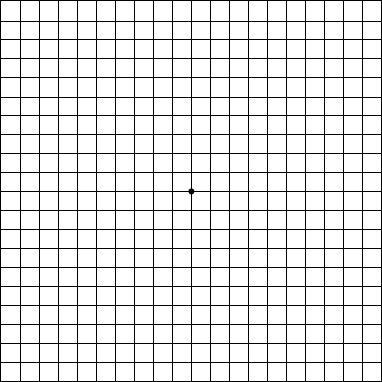

Using an Amsler grid to test for macular degeneration

If you have been diagnosed with dry macular degeneration, you should use a chart called an Amsler grid every day to monitor your vision, as dry macular degeneration can change into the more damaging wet form.

To use the Amsler grid, wear your reading glasses and hold the grid 12 to 15 inches away from your face in good light.

• Cover one eye.

• Look directly at the center dot with the uncovered eye and keep your eye focused on it.

• While looking directly at the center dot, note whether all lines of the grid are straight or if any areas are distorted, blurry or dark.

• Repeat this procedure with the other eye.

• If any area of the grid looks wavy, blurred or dark, contact your ophthalmologist.

• If you detect any changes when looking at the grid, you should notify your ophthalmologist immediately.

Wet, or exudative, macular degeneration (also called neovascular macular degeneration)

About 10 percent of people who have macular degeneration have the wet form, but it can cause more damage to your central or detail vision than the dry form.

Wet macular degeneration occurs when abnormal blood vessels begin to grow underneath the retina. This blood vessel growth is called choroidal neovascularization (CNV) because these vessels grow from the layer under the retina called the choroid. These new blood vessels may leak fluid or blood, blurring or distorting central vision. Vision loss from this form of macular degeneration may be faster and more noticeable than that from dry macular degeneration.

The longer these abnormal vessels leak or grow, the more risk you have of losing more of your detailed vision. Also, if abnormal blood vessel growth happens in one eye, there is a risk that it will occur in the other eye. The earlier that wet macular degeneration is diagnosed and treated, the better chance you have of preserving some or much of your central vision. That is why it is so important that you and your ophthalmologist monitor your vision in each eye carefully.

What Is Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO)?

The retina—the layer of light-sensitive cells at the back of the eye—is nourished by the flow of blood, which provides nutrients and oxygen that nerve cells need. When there is a blockage in the veins into the retina, retinal vein occlusion may occur.

Branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) is a blockage of the small veins in the retina. (When there is blockage of the main vein in the retina, it is called Central Retinal Vein Occlusion.)

BRVO often occurs when retinal arteries that have been thickened by atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) cross over and place pressure on a retinal vein. When the vein is blocked, nerve cells within the eye may die.

Because the macula—the part of the retina responsible for central vision—is affected by blocked veins, some central vision is lost.

The most common symptom of BRVO is vision loss or blurring in part or all of one eye. The vision loss or blurring is painless and may happen suddenly or become worse over several hours or days. Sometimes there is a sudden and complete loss of vision. BRVO almost always happens only in one eye.

BRVO is associated with aging and is usually diagnosed in people who are aged 50 and older. High blood pressure is commonly associated with BRVO.

In addition, people with diabetes are at increased risk for BRVO. About 10 percent to 12 percent of the people who have BRVO also have glaucoma. People with atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) are also more likely to develop BRVO.

The same measures used to prevent coronary artery disease may reduce your risk for BRVO. These include:

eating a low-fat diet;

getting regular exercise;

maintaining an ideal weight; and

not smoking.

If you experience sudden vision loss, you should contact your ophthalmologist (Eye M.D.) immediately. He or she will conduct a thorough examination to determine if you have branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO).

Your ophthalmologist will dilate your eyes with dilating eye drops, which will allow him or her to examine more thoroughly the retina for signs of damage. Among the other tests that your Eye M.D. may conduct are:

Fluorescein angiography. This is a diagnostic procedure that uses a special camera to take a series of photographs of the retina after a small amount of yellow dye (fluorescein) is injected into a vein in your arm. The photographs of fluorescein dye traveling throughout the retinal vessels show how many blood vessels are closed.

Intraocular pressure.

Pupil reflex response.

Retinal photography.

Slit-lamp examination.

Testing of side vision (visual field examination).

Visual acuity, to determine how well you can read an eye chart.

In addition, you may be tested to determine your blood sugar and cholesterol levels. People under the age of 40 with BRVO may be tested to look for a problem with clotting or blood thickening.

Because there is no cure for branch retinal vein occlusion, the main goal of treatment is to stabilize vision by sealing off leaking blood vessels. Treatments may include laser treatment and injections.

Finding out what caused the blockage is the first step in treatment. Your Eye M.D. may recommend a period of observation following your diagnosis. During the course of BRVO, many patients will have swelling in the central macular area. This swelling, called macular edema, can last more than one year.

Focal laser treatment is often used to reduce swelling of the macula. With this form of laser surgery, your Eye M.D. applies many tiny laser burns to areas of fluid leakage around the macula. The main goal of treatment is to stabilize vision by sealing off leaking blood vessels that interfere with the proper function of the macula. Treatment with injections of Eylea, Avastin, or Lucentis in the eye may also be done.

Retinal Detachment: What Is a Torn or Detached Retina?

The retina is the light-sensitive tissue lining the back of our eye. Light rays are focused onto the retina through our cornea, pupil and lens. The retina converts the light rays into impulses that travel through the optic nerve to our brain, where they are interpreted as the images we see. A healthy, intact retina is key to clear vision.

The middle of our eye is filled with a clear gel called vitreous (vi-tree-us) that is attached to the retina. Sometimes tiny clumps of gel or cells inside the vitreous will cast shadows on the retina, and you may sometimes see small dots, specks, strings or clouds moving in your field of vision. These are called floaters. You can often see them when looking at a plain, light background, like a blank wall or blue sky.

As we get older, the vitreous may shrink and pull on the retina. When this happens, you may notice what look like flashing lights, lightning streaks or the sensation of seeing “stars.” These are called flashes.

Retinal tear and retinal detachment

Usually, the vitreous moves away from the retina without causing problems. But sometimes the vitreous pulls hard enough to tear the retina in one or more places. Fluid may pass through a retinal tear, lifting the retina off the back of the eye — much as wallpaper can peel off a wall. When the retina is pulled away from the back of the eye like this, it is called a retinal detachment.

The retina does not work when it is detached and vision becomes blurry. A retinal detachment is a very serious problem that almost always causes blindness unless it is treated with detached retina surgery.

Retinal Detachment: Torn or Detached Retina Causes

Vitreous gel, the clear material that fills the eyeball, is attached to the retina in the back of the eye. As we get older, the vitreous may change shape, pulling away from the retina. If the vitreous pulls a piece of the retina with it, it causes a retinal tear. Once a retinal tear occurs, vitreous fluid may seep through and lift the retina off the back wall of the eye, causing the retina to detach or pull away.

Vitreous gel, the clear material that fills the eyeball, is attached to the retina in the back of the eye. As we get older, the vitreous may change shape, pulling away from the retina. If the vitreous pulls a piece of the retina with it, it causes a retinal tear. Once a retinal tear occurs, vitreous fluid may seep through and lift the retina off the back wall of the eye, causing the retina to detach or pull away.

Vitreous fluid normally shrinks as we age, and this usually doesn’t cause damage to the retina. However, inflammation (swelling) or nearsightedness (myopia) may cause the vitreous to pull away and result in retinal detachment.

Diabetic Retinopathy

The retina is a thin layer of light-sensitive tissue that lines the back of the eye. Light rays are focused onto the retina, where they are transmitted to the brain and interpreted as the images you see. The macula is a very small area at the center of the retina. It is the macula that is responsible for your pinpoint vision, allowing you to read, sew or recognize a face. The surrounding part of the retina, called the peripheral retina, is responsible for your side — or peripheral — vision.

Diabetic retinopathy, the most common diabetic eye disease, occurs when blood vessels in the retina change. Sometimes these vessels swell and leak fluid or even close off completely. In other cases, abnormal new blood vessels grow on the surface of the retina.

Diabetic retinopathy usually affects both eyes. People who have diabetic retinopathy often don’t notice changes in their vision in the disease’s early stages. But as it progresses, diabetic retinopathy usually causes vision loss that in many cases cannot be reversed.

Diabetic eye problems

There are two types of diabetic retinopathy:

Background or nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR)

Nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) is the earliest stage of diabetic retinopathy. With this condition, damaged blood vessels in the retina begin to leak extra fluid and small amounts of blood into the eye. Sometimes, deposits of cholesterol or other fats from the blood may leak into the retina.

NPDR can cause changes in the eye, including:

Microaneurysms: small bulges in blood vessels of the retina that often leak fluid.

Retinal hemorrhages: tiny spots of blood that leak into the retina.

Hard exudates: deposits of cholesterol or other fats from the blood that have leaked into the retina.

Macular edema: swelling or thickening of the macula caused by fluid leaking from the retina’s blood vessels. The macula doesn’t function properly when it is swollen. Macular edema is the most common cause of vision loss in diabetes.

Macular ischemia: small blood vessels (capillaries) close. Your vision blurs because the macula no longer receives enough blood to work properly.

Many people with diabetes have mild NPDR, which usually does not affect their vision. However, if their vision is affected, it is the result of macular edema and macular ischemia.

Watch how macular edema and macular ischemia affect your eyes.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR)

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) mainly occurs when many of the blood vessels in the retina close, preventing enough blood flow. In an attempt to supply blood to the area where the original vessels closed, the retina responds by growing new blood vessels. This is called neovascularization. However, these new blood vessels are abnormal and do not supply the retina with proper blood flow. The new vessels are also often accompanied by scar tissue that may cause the retina to wrinkle or detach.

PDR may cause more severe vision loss than NPDR because it can affect both central and peripheral vision. PDR affects vision in the following ways:

Vitreous hemorrhage: delicate new blood vessels bleed into the vitreous — the gel in the center of the eye — preventing light rays from reaching the retina. If the vitreous hemorrhage is small, you may see a few new, dark floaters. A very large hemorrhage might block out all vision, allowing you to perceive only light and dark. Vitreous hemorrhage alone does not cause permanent vision loss. When the blood clears, your vision may return to its former level unless the macula has been damaged.

Traction retinal detachment: scar tissue from neovascularization shrinks, causing the retina to wrinkle and pull from its normal position. Macular wrinkling can distort your vision. More severe vision loss can occur if the macula or large areas of the retina are detached.

Neovascular glaucoma: if a number of retinal vessels are closed, neovascularization can occur in the iris (the colored part of the eye). In this condition, the new blood vessels may block the normal flow of fluid out of the eye. Pressure builds up in the eye, a particularly severe condition that causes damage to the optic nerve.

Watch how vitreous hemorrhage affects your eyes.